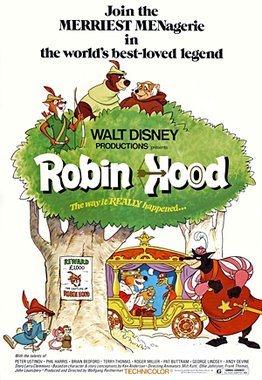

All the key players from any telling of Robin Hood's story are present. Robin Hood himself manages to be a charming protagonist, while Little John, voiced by Phil Harris, essentially comes off as a retread of Baloo from The Jungle Book, though it's not necessarily detrimental. Prince John, meanwhile, is given a comically effeminate interpretation, with Sir Hiss (basically a discount version of Kaa) practically functioning as his battered spouse; the gay subtext between the two is hard to ignore. The Sheriff of Nottingham has the potential to function as a more threatening counterpart to the foppish prince, but that potential is diluted considerably by the use of voice actor Pat Buttram, whose reedy midwest twang is decidedly non-threatening. Maid Marian is there as well, though she exists purely as a love interest to be rescued by Robin Hood, doing nothing in any of the film's (quite fun) action sequences.

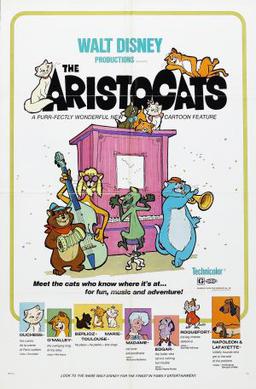

Though Robin Hood is, overall, a fun children's film (and a decidedly better one than The Aristocats), it does represent a few bizarre decisions on the part of the filmmakers, most notably with the voice acting: half the characters are appropriately English or Scottish (though their accents do seem a bit affected and less-than-genuine), and the other half speak in undisguised rural American accents, a bit confusing for a film based on a notable English legend (though not without precedent, as witnessed by Arthur in The Sword in the Stone). Additionally, the songs are chiefly American country/folk (with a bit of surf guitar thrown in during the actions scenes), and the film is narrated by folk singer Roger Miller. One is left to wonder just why Disney felt the need to subtly Americanize one of England's most iconic legends; it does detract a bit from what is otherwise an enjoyable film, though not a particularly artistically groundbreaking one.